Common & scientific name

sweetpotato / camote / kumara / batata / boniato

Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.

Description of the crop

Domesticated in tropical America at least 6,000 years BCE (Larson et al., 2014 1 ; Engel, 1970 2 ), sweetpotato is a globally important, versatile root crop that is being used as food, animal feed and processed food products around the world. Due to its hardiness, low input requirements, high yield potential and excellent nutrition, the crop plays a key role as a food security crop for subsistence farmers while attracting increasing demand among health-conscious consumers. All plant parts of sweetpotato, including roots, leaves and shoots, are edible. The roots are a rich source of carbohydrates, dietary fiber, vitamins, and micronutrients,and the protein-rich compare favorably with other leafy vegetables (Loebenstein, 2009 3 ) .

Sweetpotato is an herbaceous crop and the trailing stems or vines develop roots at the nodes and can reach up to five meters in length. The leaf shapes are diverse and appear heart, spear or lobe-shaped. The leaf colors range from light green to dark purple. The storage roots appear from white over yellow to dark orange and even deep purple (Huamán, 1991 4 ; 1999 5 ).

Orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) varieties are high in b-carotene but low in dry matter content which gives them a moist texture. White or cream varieties are starchy and typically lack b-carotene but have a higher dry matter content (>30%). The texture of these varieties is mealy, and their taste less sweet (Woolfe 1992 6 ). The less common, purple-fleshed varieties are high in anthocyanins (Cevallos-Casals and Cisneros-Zevallos 2002 7 ) .

Sweetpotato is propagated vegetatively, mostly by planting stem cuttings of 20-30 cm length and, to a much lesser extent, by using sprouted roots or root pieces. Vines can be divided into several cuttings that can be planted directly into the soil. Sweetpotato has a short cropping cycle of 90-120 days, but early maturing varieties can grow even faster while traditional varieties may require more than 150 days. The crop is perennial and can be left in the ground, though extended cropping periods foster the accumulation of pests (e.g., weevils) and diseases and decrease root quality. Yet subsistence farmers sometimes prefer piecemeal harvests to keep roots fresh or to guarantee a constant supply of green leaves as vegetables or animal feed (Huamán 1999 5 ; Stathers et al. 2013 8 ).

Economic, cultural and food security importance

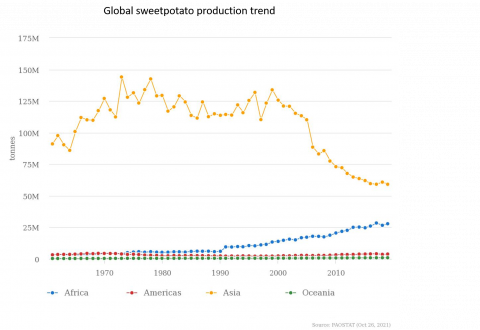

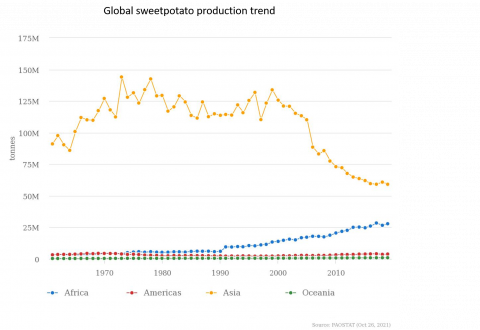

Sweetpotato is the seventh most important food crop globally with more than 91 million tons produced in 2019, grown on about eight million hectares of land. Asia accounts for 64% of global sweetpotato production, Africa for about 30%, and the rest of the world together for 6%.

Sweetpotato has great potential to contribute to reduced hunger in the world because of its nutritional value exceeding most carbohydrate food crops in vitamins (A, C, B1, riboflavin, niacin, B6, E, biotin, pantothenic acid), minerals (potassium, copper, manganese and iron), fibre and protein content (Wang et al. 2016 9 ; Alam 2021 10 ).

Being an excellent source of beta-carotene orange- and yellow-fleshed sweetpotatoes have been successfully promoted to reduce vitamin-A deficiency in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of world (Islam et al. 2016 11 ; Neela et al. 2019 12 ; Girard et al. 2021 13 ). Consumed and locally traded as fresh product (leaves and roots) by smallholder farmers in subsistence economies, the crop is also used to feed animals and produce processed food such as chips, snacks, noodles, or biscuits and is becoming more popular in the northern hemisphere where it is considered a healthy superfood.

Status of genetic resources

The genebank at the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru holds the largest sweetpotato collection in the world with more than 7,500 active accessions, including traditional and improved varieties, breeding lines and crop wild relatives. The diversity that is conserved ex-situ is an important reservoir from which the global community can draw to contribute to food security through breeding, research, and training.

While the exact center of origin and domestication of sweetpotato is still controversially discussed, several genetic diversity studies support the hypothesis that the region encompassing northern South America, Central America and the Caribbean is the primary center of diversity of sweetpotato while both Papua New Guinea and East Africa form important secondary centers of diversity (for review see Jarret et al., 2021 14 ).

Despite the large number of sweetpotato accessions maintained at CIP and other genebanks, these collections represent only the tip of the iceberg as the large majority of landraces and traditional varieties are still exclusively conserved in farmers’ fields. Unfortunately, comprehensive and systematic baselines studies of sweetpotato conserved on farm are extremely few. From the studies that are available, the in-situ diversity of landraces at country level reveals an impressive degree of diversity (Bourke 2009 15 ; Karuri et al. 2010 16 ; Tumwegamire et al. 2011 17 ; Zawedde et al. 2014 18 ).

Further information covering all relevant sweetpotato topics can be accessed here.

- 1 Larson, G., Piperno, D. R., Allaby, R. G., Purugganan, M. D., Andersson, L., Arroyo-Kalin, M., ... & Fuller, D. Q. (2014). Current perspectives and the future of domestication studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(17), 6139-6146. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323964111

- 2 Engel, F. (1970). Exploration of the Chilca canyon, Peru. Current Anthropology, 11(1), 55-58. https://doi.org/10.1086/201093

- 3 Loebenstein, G. 2009. Origin, distribution and economic importance. In: Loebenstein, G., Thottappilly, G. (eds.) The Sweet Potato, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 9-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9475-0_2

- 4 Huaman, Z. (1991). Descriptors for sweet potato. Descripteurs pour la patete douce. Descriptores de la batata (No. C027. 041). International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR). https://www.bioversityinternational.org/fileadmin/_migrated/uploads/tx_…

- 5 a b Huaman, Z. (1999). Sweetpotato Germplasm Management (Ipomoea batatas). Training manual, 218. Lima, Peru: International Potato Center (CIP). http://www.sweetpotatoknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Sweetpotato-Germplasm-Management-Ipomoea-batatas-Training-Manual.pdf

- 6 Woolfe, J. A. (1992). Sweet potato: an untapped food resource. Cambridge University Press

- 7 Cevallos-Casals, B. A., & Cisneros-Zevallos, L. A. (2001, November). Bioactive and functional properties of purple sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam). In I International Conference on Sweetpotato. Food and Health for the Future 583 (pp. 195-203)

- 8 Stathers, T., Carey, E., Mwanga, R., Njoku, J., Malinga, J., Njoku, A., Gibson, R., Namanda, S. 2013. Everything you ever wanted to know about sweetpotato: Reaching Agents of Change ToT Manual. 4: Sweetpotato production and management; Sweetpotato pest and disease management. International Potato Center (CIP), Nairobi, Kenya, vol.4. https://doi.org/10.4160/9789290604273.v4

- 9 Wang, S., Nie, S., & Zhu, F. (2016). Chemical constituents and health effects of sweet potato. Food Research International, 89, 90-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2016.08.032

- 10 Alam, M. K. (2021). A comprehensive review of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam): Revisiting the associated health benefits. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 115, 512-529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.07.001

- 11 Islam, S. N., Nusrat, T., Begum, P., & Ahsan, M. (2016). Carotenoids and β-carotene in orange fleshed sweet potato: A possible solution to vitamin A deficiency. Food Chemistry, 199, 628-631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.057

- 12 Neela, S., & Fanta, S. W. (2019). Review on nutritional composition of orange‐fleshed sweet potato and its role in management of vitamin A deficiency. Food science & nutrition, 7(6), 1920-1945

- 13 Girard, A. W., Brouwer, A., Faerber, E., Grant, F. K., & Low, J. W. (2021). Orange-fleshed sweetpotato: Strategies and lessons learned for achieving food security and health at scale in Sub-Saharan Africa. Open Agriculture, 6(1), 511-536.https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2021-0034

- 14 Jarret, R.L., Anglin, N.L., Ellis, D., Villordon, A., Wadl, P., Jackson, M. 2019. Sweetpotato genetic resources: today and tomorrow. Burleigh Dodds, Cambridge, UK. ID 9781786764348, pp. 1-52

- 15 Bourke, R.M. (2009). Sweet potato in Oceania. In: Loebenstein, G., Thottappilly, G. (eds.) The Sweet Potato. Springer, Berlin, pp. 489-502

- 16 Karuri, H. W., Ateka, E. M., Amata, R., Nyende, A. B., Muigai, A. W. T., Mwasame, E., & Gichuki, S. T. (2010). Evaluating diversity among Kenyan sweet potato genotypes using morphological and SSR markers. Int. J. Agric. Biol, 12(1), 33-38

- 17 Tumwegamire, S., Rubaihayo, P. R., LaBonte, D. R., Diaz, F., Kapinga, R., Mwanga, R. O. M., & Grüneberg, W. J. (2011). Genetic Diversity in White‐and Orange‐Fleshed Sweetpotato Farmer Varieties from East Africa Evaluated by Simple Sequence Repeat Markers. Crop Science, 51(3), 1132-1142. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2010.07.0407

- 18 Zawedde, B. M., Harris, C., Alajo, A., Hancock, J., & Grumet, R. (2014). Factors influencing diversity of farmers’ varieties of sweet potato in Uganda: implications for conservation. Economic botany, 68(3), 337-349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-014-9278-3